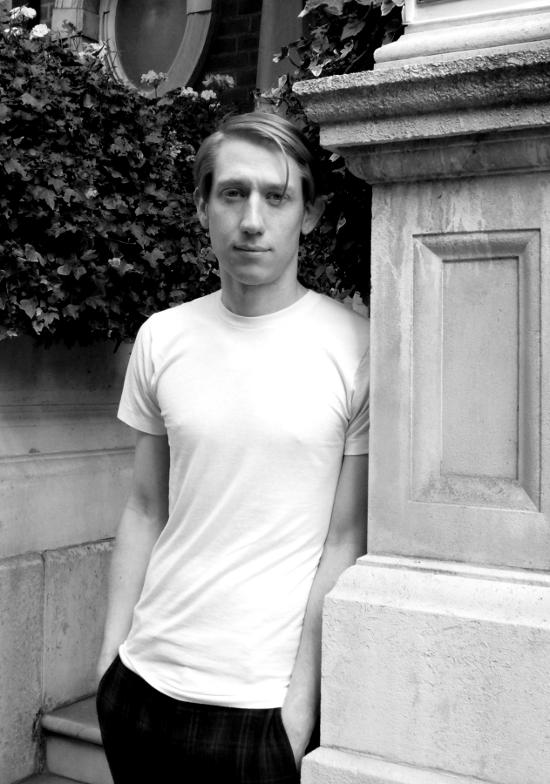

Scott Treleaven is perceived as a special kind of Queer Revolutionary. From zines and films to photography and installations the Canadian artist never seized to hide his interest on subcultures, the occult, secret rituals and mystical symbols. During his interview we discussed about some of his most well known – recent and past – art projects as well as his collaborations with AnOther Magazine and artist AA Bronson.

-What was it like growing up in Toronto and how has the local art scene affected your work?

Toronto was a great place to grow up. It had a particularly vibrant underground scene in the nineties, when there was a lot of activism, an aggressive queer presence, and a lot of indie culture. It’s still an excellent place to work, being relatively comfortable and inexpensive, but unfortunately it was starting to become increasingly insular by the time I’d left. I don’t know why, but there was never a lot of international outreach or crossover, or if there was it wasn’t sustained.

-How did The Salivation Army zine and the short film The Salivation Army, screened at MoMA and Art Basel among others, occur as an idea?

The Salivation Army came to me as a dream in 1995. In the dream three boys introduced themselves to me as ‘the Salivation Army’, an occult homo-punk gang, and told me that I was meant to bring the gang into existence. So I did. The zine and film were an attempt to create a functional, open mythology from the ground up. It also holds a few of the nascent concepts that drive my work now.

-How have William Burroughs, William Blake, Brion Gysin and Derek Jarman affected you as a person and an artist?

That’s impossible to summarize but if I could think of one thread that connected them all it would probably be their conviction as artists; the things that they wrote and made were all sincerely motivated. They all believed that art was a vital, evolutionary strategy, meant to elicit a real transformation in both the artist and the viewer, and not merely a vehicle for bourgeois entertainment or popularity. It’s funny to think, regardless of what people like to pretend now, that in their lifetimes they were all pretty much despised by the establishment because of these beliefs.

-You have said that ‘the occult for me has always been a more accurate and dignified way of describing the human conditions’.

What is your relationship with magic now taking into account your recent project for C Magazine? Which occult symbols appear most frequently in your work?

The project for C Magazine hinged on a very insightful essay on my work by the writer and artist, Elijah Burgher. He has a very unique perspective on my work because of his own interest in some of the same ideas. Personally though, my foremost concern is with the anomie, so to speak, in things like subcultures and the more rarified types of human experience that include, but aren’t restricted to, the occult. It might be more succinct to say that my art is more rooted in cultural anthropology and psychology, than it is in magic.

-In 2009 you did Cimitero Monumentale, a photographic edition for Printed Matter, including black and white photographs of sculptures and gravestones. Why do you think cemeteries, an otherwise considered morbid space, and particularly cemeteries strolls carry such an intriguing and fascinating notion?

I like graveyards, I’ve always found them great contemplative spaces -probably because they put everything into perspective- but I’d never seen anything like the Cimitero Monumentale. I was living in Milan for three months, and became totally obsessed with it. I’d visit it twice or three times a week, and try to dissect the complicated sensations it was provoking in me. The documentation of the statuary started as a private endeavour at first, and not something I’d intended to show. It was only when I started to talk about them with AA Bronson that he suggested I make the edition. It was a great idea, of course, and it stands as a kind of open ended examination of things like finitude, vanity, tenderness and memory…but even then, after working so closely with the photos I felt that they didn’t quite articulate the experience, which lead me to a series of drawings that I showed in Los Angeles earlier this year.

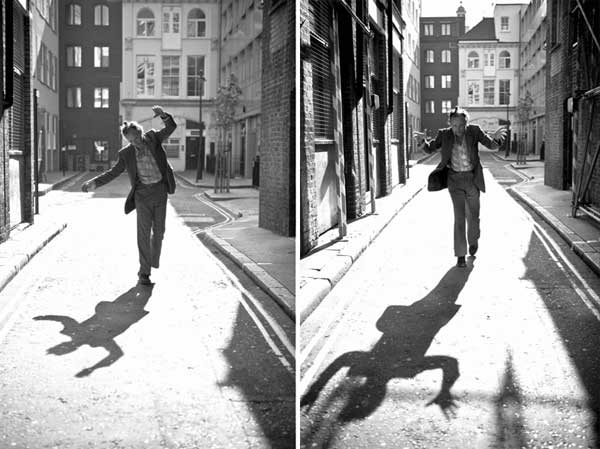

-Issue 10 of AnOther Man Magazine has included a project of yours: A 14 page photographic editorial with stylist Alister Mackie.

-What is your relationship with fashion and how do you feel about this project?

I read Dick Hebdige’s Subculture: The Meaning of Style when I was teenager and that still shapes a lot of my attitude towards fashion to this day. Or, as my friend designer Marco Zanini often notes, ‘fashion is a language.’ The AnOther Man shoot was a great project, and I loved having the opportunity to work in a different vernacular, and to see if I could bring my own agenda to it. Alister was a lot of fun to work with, very perceptive, very smart, and we played with a lot of styles and images that fell somewhere between the veneration and satirizing of luxe culture. It’s funny, but there was a luxury multi-brand website that had picked up the images for a few days before getting timid and dropping them. I’d wanted to make the photos beautiful, without being mindlessly digestible, so I took it as a sign that I’d probably succeeded.

-You work with the Breeder in Athens that also represented you in the Armory Show last summer. What is your opinion of the contemporary Athenian and generally Greek art scene?

The Breeder are a terrific gallery to work with, but I’ve had limited personal experience with the Greek art scene itself, so it’s hard to comment. Athens was a pretty amazing city to visit, though. I’ve been twice now, and there’s always a palpable kind of energy there – very dynamic. I’m not obliquely referring to any kind of social or political situation, either. I just felt an excitement, like almost anything could happen there. For an artist, for anyone really, being able to feel that air of ‘permission’, so to speak, is rare.

Text: Kika Kyriakakou | Photo: Paul P. | Links: ScottTreleaven.com , thebreedersystem.com