The Santorini Arts Factory (SAF) sits shaded cooly by gently shifting cliffs, the faces of which have been softly scooped and scraped at by the elements; the slowest and most gentle sculpture. SAF appears neither flat nor crooked, but rather drifting between states of varying continuity, deciding at once to adhere to the streamlines of planes ahead, and the gentle ebb and flow of the sea; both audible between its curvatures; both a deep blue. SAF had once been a unique tomato factory, and upon entrance, SAF draws you into a tilting square. From one side, the Tomato Industrial Museum “D. Nomikos” reclines as a direct testament to its history, and from the other a series of doorways beckons its visitors toward Project Removement; a visual arts project, running from June until September.

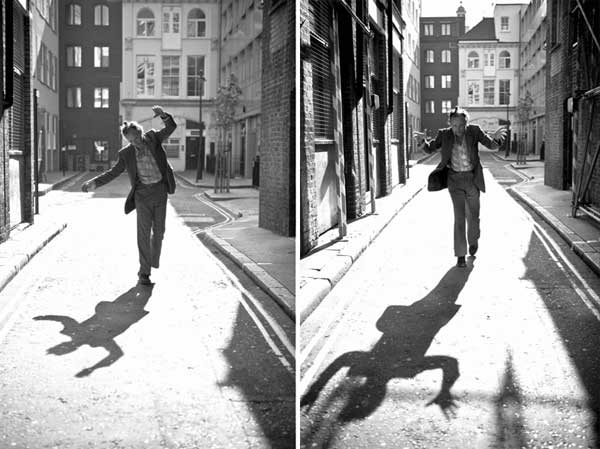

Curated by Maria Vasariotou, Project Removement “aims at interpreting, attributing and synthetically presenting motion or/and alteration, which characterizes a land, through the creative utilisation of mixed media”. Quite a statement, and one which promises a myriad of seemingly conflicting conceptions, be these natural/synthetic, static/chaotic, or rational/artistic. However, upon entrance one is quickly inhaled by this world of opposites, impossibility, and distorted expectations. This realm is the result of a number of artists, and includes two solo installations from each of the established Zilvinas Kempinas and Yorgos Maraziotis, one lighting and video installation by Stella Bolonaki, and one group installation headed by Georgia Damianou, Olga Bogdanou, Anna Maria Samara, and 29 students and graduates of the Department of Fine and Applied Arts of Florina. Each installation negotiates the aims of Project Removement with integrity and stylistic flair, something which I may only give a sense of, but in order to experience one will have to visit Santorini’s newest and most intriguing exhibition.

Zilvinas Kempinas’ is perhaps the most immediately striking of the four installations, due simply to his direct and astounding manipulation of the room. The threshold meets what, at first glance, appears to be a floor-level fountain filled with black oil, but is in fact one of Kempinas’ fan-sculptures; of which there is another sharing the space: two fans pointing directly toward one another with two rings of tape suspended by their battling winds. Both of these fan-sculptures distort reality; fooling the eye with violent revolutionary movement. One of the main materials used by Zilvinas Kempinas is air, an invisible yet integral piece of his work. The rest is black plastic, a cruel and unpleasant looking substance which is manipulated so beautiful by the wind that one cannot help but be amazed at this interplay of synthetic and natural, especially indoors where elements cannot hold such control over the inhabitants. The artist’s interest in revolution (cyclical and repetitive movements) and natural/synthetic conflict is nicely tied together by the two light box constructions, which – together with the fan sculptures – draws a nice line across the room. These light box constructions appear to resemble both the moon and the human ovum, two fundamentally cyclical forces, one over the natural tidal forces, and the other the internal biological creation environment. Both are considered feminine images. However, where the ovum holds an innate femininity, the moon has inherited it from human poetic and cultural association (perhaps, a more synthetic femininity). Kempinas’ installation offers us a stark conflict; a sense of confusion and other-worldliness, within an all too present state of being.

“STILL” by Yorgos Maraziotis is a more complex and subtle artistic interrogation. We see a direct contrast with Kempinas’ installation, for when one enters Maraziotis’ one is struck by the silence. Yorgos described this silence as like that of an alter, an almost religious stillness. Indeed, the way Maraziotis draws his visitors through his long and softly inclined space, it is as if one is being beckoned upward. In a literal sense also, for the room’s centre piece is separated by a wall and a short staircase. One must climb and be pushed out onto a plinth into an abyss before this statement of eternity, to face the white light “Forever“‘. Yorgos is similarly experimenting with contradicting ideas, of imprisonment and freedom, of softness and hardness; the light of ‘Forever’ is a neon-realisation, and one which is all too temporary for its name (as not even a three month long installation can live up to such a title). One is forced to question the reality of eternity, in fact, one must question the reality of all of Maraziotis’ pieces; for each resembles something which it is not. A soft white pillar rises from the centre of the room, and appears to be brimming with a similar black oil to that of Kempinas’ fountain; but is in fact solid. Three clipped sculptures of ruined paper, actually made of canvas, adorn the wall to its left, and roughly opposite them a small sculpture of jagged rocks, made from a glimmering precious-looking substance. Maraziotis halts the breath with his work, makes one question their interpretations, and shows a stillness and softness in the harsh or moving. A beautiful reflection of Santorini, and one which shows that Yorgos thought a lot about displaying these pieces on this particular island, for his entire installation embodies the same still movement integral to the unique volcanic island. An activity of heat and heavy shifting beneath the surface, a harshness; but above ground a gentle breeze of life, of coming and going. The entire thing held together by a stillness of concept, for this truth remains true despite those who come and go, Santorini remains relatively fixed in its place. The active volcano, he explains, makes Santorini’s citizens question the longevity of their home, and that’s why ‘Forever’ works so well here, because it pushes the idea of the temporary, of questioning life. Yorgos’ works are clearly about pushing limits, but these limits are broken with a subtle intelligence beyond the artist’s years; a philosophically racing mind beneath a still, calm, and collected wisdom.

The rest of the exhibition was equally intriguing, not least because of the way that each artist seemed to feed so nicely into another. There is a definite congruity between the works, and yet an obvious separation of artistic license and conceptualization of the overarching object of Project Removement. The group exhibition offered a great wave of work, which spanned the entire warehouse space, and made one feel like one was walking the ocean bed up to the shore; an indeterminate line between visitor, artist, and artwork, drawing the room into a quiet chaos. A particularly striking point of note was that admirers of the art were allowed to strip back a page from hanging books of work and take it out of the installation with them. A controversial move, but one which could be considered an insightful statement on installation art in and of itself. For if an artist is to be displayed, another work must be removed from display. The group managed to exercise a surprising level of continuity between their work, for when a group of over 30 people are working on one installation, one expects a conflict of interests. In fact, the group work, and the exhibition as a whole went off without a hitch; perfectly accompanied by good local wines, cheeses, and conversation.

OZON Magazine would like to extend a massive thank you to all those made Project Removement possible, the SAF Gallery, and to everyone who made our stay beautifully fulfilling.

*Words by Oisin Fogarty Graveson.