Lucas Simões, Sao Paulo based artist, has a style few can rival in terms of originality. Having studied architecture and design, Simões’ education shines through his work; the geometric distortion and deconstruction, elements of much of his art, evocative of digital graphic work, and building design.

#1: Lucas, your website informs its readers that you use “source materials such as maps, books and photography”, folding, cutting, and generally distorting these to new, more interesting forms. Why did you lean towards this artistic strategy, rather than more traditional drawing techniques?

Before all this a did a lot of painting and drawing, but it got to a point where I found that some ideas needed a different approach in order to accentuate their strength, so I started dabbling with other things. So the first step was to play with concepts that already carried a meaning (like books, maps and photographs) and it was really inspiring to me. In the end, I found myself done with the printed image and started to think of space itself as a raw material for my experiments. It’s not that I don’t imagine myself making paintings again. For me, artistic research is a spiral path, where we include many different techniques, which when coupled with our own historic experience, lead us to new things.

#2: Where do these materials come from? Do you pick up anything you like the look of, and play around with it until something catches your imagination; or does the finished idea come first, then you go scavenging?

Yes, that’s it, I usually collect many materials and experiment with them in my studio, until it takes on a new meaning for me, that can be conceptual or aesthetic, and then I start working on the possibilities of it. It’s a slow process, a hugely experimental one too, until I’m finally satisfied with the result.

#3: Your work teeters on the edge of the beautiful and the strange. What are you trying to say by altering objects into new forms? Is there a message, or is it purely aesthetic?

For me it’s more of a sensory message that starts from an aesthetic platform. Many of my works make people feel like touching it, because they present a new use for a common object. It’s my way of questioning the sensory memory of everyday things like plastic bags, Styrofoam, paper, etc. I create a topographic architectural situation for them, so they are also disconnected from their usual state, sometimes gaining an architectural scale. In my last exhibition “The weight, the time”, some people called me sadistic, because all the works were really appealing to touch, but there was a ‘do not touch’ sign there, due to gallery politics.

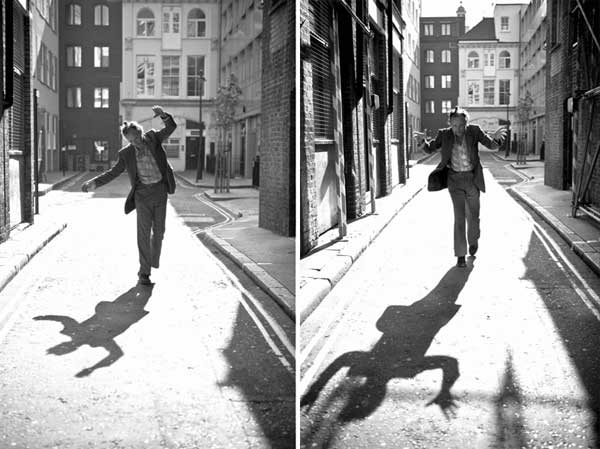

#4: OZON recently stumbled across your ‘Desmemόrias’ photos, the geometric recreation of which really struck us as quite beautiful. There’s something haunting about the brutal distortion of the human face, something which you do repeatedly in this collection. What’s the story behind these photos? Are the people behind the picture important, or is it more the overlay of cuts and shaping that is the subject here?

I made two different series using cut out portraits, and both of them led to the same point: ‘Unportratis’ and ‘Unmemories’ (Desretratos and Desmemόrias). In the case of the Unportraits, I invited close friends over to tell me a secret as I took their portrait. However, my intention was not to hear their secret, but to capture the expressions of each person in the moment when they revealed their secret. So I asked each of them to choose a song for me to listen to in my headphones while I photographed them. After the photo session, I asked each of them if the secret had a color, and these are the colors that the portraits carry. Each photo session generated between 200 and 300 photos, of which I chose 10 different portraits, treated each image with the “color” of the secret, and then printed them, in order to start the cutting process. I created each cutting pattern according to the person photographed, a subjective concept, my personal interpretation of the person or perhaps the moment in which they were photographed. The reasoning behind it was so I could always see a piece of each portrait as it is layered and so no portrait is divided into two separate pieces. The last photo is always whole, without any cuts, and then each subsequent photo is gradually cut. Those closer to the bottom have fewer spaces cut out and those nearer the top are almost entirely cut, leaving practically only the border. As for the Unmemories series, the rationale is a bit different. I photographed old childhood friends with whom I no longer maintain contact and also random individuals I had just met. In this case, I found their contact details and called them for a conversation. The portraits were made during this conversation, but in this case with no songs or secrets. From this encounter, I also separated 10 photos of each person and, for the most part, did not treat them with any particular color in mind, leaving the color and light as they were at that moment, without any treatment. The basic cuts for these photos are more geometric and appear to be a continuous pattern, but they actually do not repeat, though they do complement each other. In both series, when the work was finished, it was no longer possible to view the face of the person photographed. It was no longer a flat portrait; it was an object with depth, created through the layering of the acrylic sheets and the different photographs.

#5: What are you working on now? Will you venture in political/social territory, or are you going to keep doing what your doing?

I just came back from Recife, I was there to make a residency, the result of which was a solo exhibition at the Modern Museum of the city. It was an interesting experience. Before going to Recife I had research projects in mind, but then when I arrived there it turned out completely different, especially because the city is now struggling to find avenues for cultural investment. The title of the project I developed was “Desert”, which is a reference to a bar that existed in Recife during the 60s, as described in the diaries of Tulio Carella, a place where he was a regular costumer, where he would meet prostitutes, homosexuals, drunks and the art crowd. Τhe museum is currently situated in a historic location, an urban, run down area of the city that is scarcely visited by the public throughout the day. So, using flashing lights and an electronic announcement board in the museum façade, I created a situation that attracts people’s attention to the current state of the area. That is to say, it’s current run down condition, but also the possibilities it carries, something that all similar historic locations have. Inside the museum, I covered and packed the exhibition panels with the same plastic tents that the street merchants that surround the area use, a way of pointing out that the museum should be more focused on that part of the population in that area. This residency experience showed me that art has to face the possibilities and conditions it finds itself in, and use the elements it finds as the driving force behind each work.

#6: You have a really unique style. That’s obvious. Who would you say inspired this? For anybody inspired by you, who else would you recommend researching?

Well, many things influence me. Literature, movies, the city, the protests, but mostly the people that are close to me, my friends and my lovers, whom I can have deep conversations about anything, and discuss my point of view.

Interview by Oisin Fogarty-Graveson